PyBox Relaunch

A much too long time has passed since I blogged the last time. I guess the main reason for this is that I’ve been pretty busy with #DAYJOB for the last half year and while I did several things I considered blog-worthy, I just didn’t put in the extra effort to go for an appropriate write-up.

This is not going to be a late new year resolution but I sincerely want to be more active again in terms of releases. I’ll be likely going for smaller, incremental posts (like I did during the main IDAscope development) as these are easier to bring to an acceptable level of quality. If there is interest, I might also start covering more concrete malware analysis content but I have been reluctant towards this so far.

Today marks a milestone for an old project of mine. I have migrated the repository of PyBox from googlecode to bitbucket since googlecode has been more or less killed by disabling new downloads earlier this month (Git > SVN anyway).

I wanted to do the migration: for half a year, but now I finally had the time needed to accompany it with a little story of what PyBox is and how we got there.

In the same run, I compiled the DLL and pydasm for the two most recent versions of Python 2.7.

I hope that there is the one or the other interesting aspect in the code that might find usage elsewhere.

Maybe PyBox by itself is interesting enough to know about as well. ;)

History of PyBox

Back in0 when Felix Leder was still at University of Bonn, he thought it would be great to have a highly customizable analysis framework and sandboxing tool for daily malware analysis.

I guess he was inspired by the outcome of the Project Honeynet Google summer of code (GSOC) project Cuckoo sandbox for which he was an advisor at that time. :)

The idea behind Cuckoo has always been to inject a DLL into a target process and have that DLL serve as a platform for monitoring.

In Cuckoo, the DLL is setting up a number of hooks for interesting Windows API functions.

Later during execution, when hooks are triggered, the logging results in a sequence of calls to their target functions including the respective parameters.

PyBox is based on the same idea.

As with Cuckoo, a DLL is injected into a target process to serve as a platform.

However, upon injection, the PyBox DLL starts a fully fledged Python interpreter within the target process, allowing the execution of arbitrary Python scripts within the context of that process.

Since Python is a great language for rapid prototying, this approach allowed us to quickly design analysis modules, e.g. custom sandboxes, tailored to certain aspects of chosen malware families.

Lately I’ve noticed that a similar concept is being realized by Frida, but using Javascript instead of Python.

PyBox architecture

In the following, I’ll explain the architecture of PyBox when being used as a sandbox, its original intended use case.

Injection

As mentioned earlier, the core of PyBox is being injected as a DLL (./DLL/PyBox.cpp) into a target process, so we first need an injector.

It is located at ./src/injector.py and the approach realized here is pretty straightforward.

If the target process does not exist yet, start it (optionally suspended). For injection, first get a handle to the process (kernel32!OpenProcess), allocate some memory in it (kernel32!VirtualAllocEx) to store a string holding the path to our PyBox DLL (kernel32!WriteProcessMemory).

Finally, use our good old friend kernel32!CreateRemoteThread to start a thread within the target process with kernel32!LoadLibraryA and the PyBox DLL path as argument.

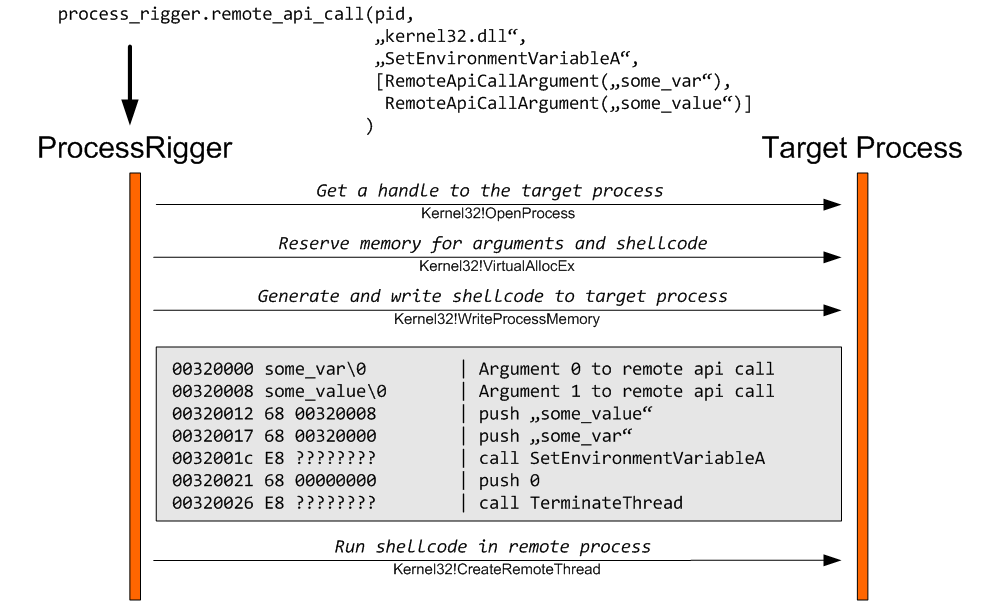

For some side tasks, we use the module ProcessRigger (./src/process_rigger.py).

For example, in order to easily perform follow-up tasks, it’s nice to grant our injector and the target process the privilege SE_DEBUG.

A more interesting functionality implemented in ProcessRigger is its ability to execute an arbitrary API call in the context of the target remote process.

For this, we dynamically generate and write a short shellcode to the target process, consisting of the expected number of push instructions as arguments (either immediates or pointer to strings / structures) and the desired call to the target API as well as a consecutive call to kernel32!ExitThread. Nothing new, but useful.

For PyBox, we only use this to set some environment variables in the context of the target process in which PyBox is injected, but since I think the concept has potential for more, here is sample code and a diagram:

PyBox DLL

When the DllMain() of PyBox is loaded in the target process, it will first check the presence of said environment variables, proceed to open a file for logging and then initialize the Python interpreter.

The PyBox DLL additionally makes itself available to the interpreter environment as an embedded module, enabling easy access to some native system functionality, like access to the process environment block (PEB), enumeration of exports for other DLLs, hook/callback handling and emergency termination.

Finally, the PyBox DLL will hand over control to the target “box” starter script (example: ./src/starter.py) which then executes the desired analysis functionality.

PyBox API

As just mentioned, PyBox is intended to be used with independent “boxes” that are specialized for certain purposes.

These boxes are powered by the functionality provided through the PyBox API.

First, there is MemoryManager (./src/pybox/memorymanager.py), granting access to memory manipulation functions in the process address space via Python ctypes. A bunch of convenience functions automatically handles read/write permissions of given memory to enable read/write operations.

Next, there is the ModuleManager (./src/pybox/emodules.py), which enumerates all other loaded DLL files (= executable modules) in the target process’ address space in preparation of hooking. The enumeration is done through the embedded module provided through the PyBox DLL itself, in order to speed up this procedure.

The PyHookManager (./src/pybox/hooking.py) provides an interface to PyBox’ hooking functionality: add and remove hooks, check if an address is already hooked (similar addresses can be hooked with multiple hooks, which are then executed in chain), and selecting the appropriate hook through its function find_and_execute().

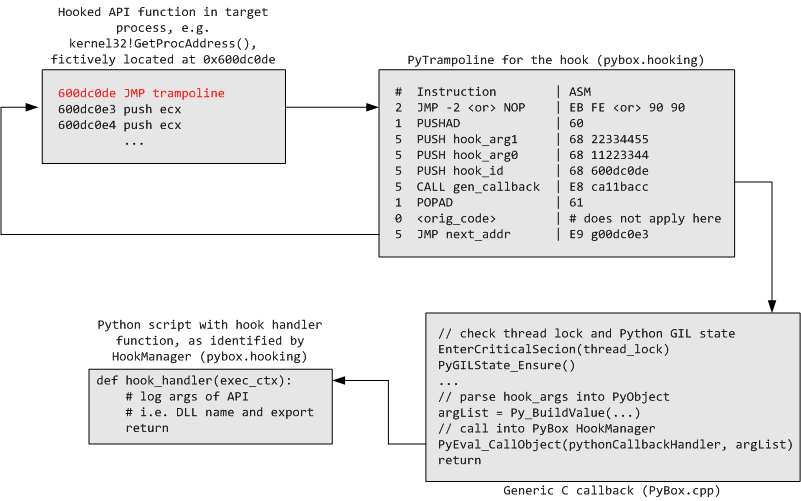

The reason for this last function is that all hooks are first pointing to the same callback address in the PyBox DLL which handles mutual exclusion (as well as the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) of Python) prior to transferring control to the hook code implemented in Python.

There exist three classes of hooks: PyFunctionEntryHook, PyReturnAddressHook, and PyHookClone.

When a new PyFunctionEntryHook is created for a target address (e.g. an Windows API function), up to 20 bytes of memory are read and disassembled via pydasm.

The reason for this is that we need to overwrite 5 bytes for a jmp instruction to our hook trampoline (PyTrampoline) while preserving the integrity of the modified code.

If more than 5 bytes are taken, the rest is padded with NOP { 90 } instructions.

For most Windows API functions, we run into no trouble as they usually start with move edi, edi; push ebp; mov ebp, esp which sums up to exactly 5 bytes but this may not the case for arbitrary other functions.

A PyReturnAddressHook is realized by overwriting the original return address of a function with a PyTrampoline address.

A PyHookClone is used when hooking one address with multiple hooks and references the original first hook.

The PyTrampoline is a dynamically generated shellcode, preparing the call of a hooking function.

It is optionally prefixed with a jmp <self> { EB FE }, which turns out useful when writing a box for unpacking.

It can be used with the intention to intercept the control flow before OEP is reached (in order to attach a debugger and proceed manually).

Next the current register state is saved (PUSHAD { 60 }) and an identifier for our hook is pushed (this allows to differ multiple hooks on the same address).

Hooks can optionally be used with their own parameters, so these are positioned with a PUSH { 68 11223344 } now.

Finally, a CALL { E8 ca11bacc } to the hook function is made.

When the hook returns, the register state is restored via POPAD { 61 } and any original opcode bytes saved during overwriting the target address when setting up the hook are executed.

Finally we JMP { E9 001dc0de } back to the instruction behind the originally hooked address.

In summary, hook execution looks like this:

When a hook is called, it can access and modify the current function execution context (return addr, stack) and register context (from EAX to EDI) through two respective objects passed to it as argument.

Besides these modules, there is also an unfinished dumper module and a ProcTrack module, which hooks API functions for spawning new processes and injects the current box into these when triggered.

Box Scripts

I have included two sample boxes in the version pushed to the repository.

The first example is the standard sandbox (stdbox), which hooks a range of interesting API functions one would be interesting in when tracing the execution of malware.

I have gone for a harmless example and traced the creation of a new file on disk through notepad.exe (uploaded here).

Most of the lines in the log file are noise, important are these:

2014-01-29 12:05:59,878 - INFO - kernel32.dll.CreateFileW(\

C:\Documents and Settings\redacted\Desktop\test.txt,\

0x80000000, 3, 0, 3, 0x00000080,0)

[...]

2014-01-29 12:05:59,898 - INFO - kernel32.dll.CreateFileW(\

C:\Documents and Settings\redacted\Desktop\test.txt, \

0xc0000000, 3, 0, 4, 0x00000080,0)

2014-01-29 12:05:59,898 - INFO - kernel32.dll.WriteFile(\

0x00000138, 0x000e0db8, 0x0000000c, 0x0007faf0, 0x00000000)

As you can see filename is test.txt on the desktop.

The first call to kernel32!CreateFileW with GENERIC_READ access and CREATE_ALWAYS|CREATE_NEW flags create the file.

The second call with GENERIC_READ|GENERIC_WRITE access and OPEN_ALWAYS flags opens the file for writing.

This is ultimately followed by kernel32!WriteFile putting the bytes just a test in there.

The second example is the more useful RWX box.

This box will only log calls that being made from RWX memory.

The idea behind this would be e.g. PyBox injection into explorer.exe in order to monitor the behaviour of malware self-injecting into that process.

Once again here is an example, this time of Citadel injecting into explorer.exe.

- In lines 8-813 you can observe Citadel creating its dynamic import table within the context of explorer.exe.

- In lines 817-1137, Citadel creating hooks itself for a range of Windows API functions.

- In lines 1138-1271 you can see Citadel starting some threads and guess about their intention (

ObtainUserAgentString-> mimic target system’s browser,WABOpen-> crawl address book for email addresses). - From line 1272 on, you can observe Citadel searching for other processes to inject into.

- Finally, from line 1372 on, Citadel found a target and injects itself.

I have included a startup batch file for both boxes so you can easily try them out.

These boxes are rather generic and simple, but it should be easy to imagine that more powerful use cases for automation can be covered (conditional controlling and patching of “interesting” memory).

More advanced stuff was shown by Felix in his talk at Troopers conference in 2011, e.g. how to intercept network payloads before they enter an SSL connection (FireFox) or how to analyze obfuscated PDF exploits by pyboxing Acrobat.

Conclusion

So that’s my short intro to the PyBox framework. Notice that it only works up to WinXP since we are practicting evil process/memory voodoo here and there that does not like modern memory protection mechanisms.

Currently, there is also no intention to further pursue development of this framework unless there will be unexpectedly huge interest in this. ;)

Hopefully some of the design or implementation details may be of interest to some of you so the PyBox spirit can live on!